Experiment!

Last week, I listened to an excellent webinar from Lean Frontiers hosted by Oscar Roche of the TWI Institute.

Three managers from Helena Industries in Des Moines, Iowa, described a packaging failure that cost the company time, money, and customer goodwill. To solve the problem, they began by developing work standards in the Kato sequence: build an operational definition of what the customer expects; define the settings and conditions for the packaging machine and inputs; and define the sequence and key points of critical steps performed by the operators. Throughout the development of their work standards, they experimented with definitions and details to ensure the packaging had leak-proof seals. They compared predictions with results. They revised their ideas and tried again, shaped by their test results. The Helena managers exemplified learning by doing.

Pocket Cards

During World War II, the Training Within Industry (TWI) program taught three core supervisory methods:

how to instruct someone to do a job safely and correctly;

how to improve a job (Job Methods);

how to handle people problems (Job Relations).

The TWI methods each use a four-step structure, making them well-suited for small pocket cards to guide daily practice.

More Methods that can fit on a pocket card

Over many blog posts, I’ve explored three other basic methods that almost anyone can learn and practice without extensive study or an academic background.

These methods also fit onto a pocket card:

experiment: try and reflect

visualize process performance: plot the dots

listen to people: ask plus-delta

Organizations that want to move ideas into wider practice will benefit from a cadre of people who are supported to regularly try and reflect, visualize process performance, and listen to others.

Another client is investigating the establishment of a learning health network. Again, network organizations will make better progress and contribute more to the network if more people practice basic pocket-card methods.

Enhancing pocket-card experimentation

Earlier this fall, I worked with several colleagues to review approaches for translating an initial idea into a demonstration of effective change that can benefit many organizations and teams. We reviewed design models that share the same advice: build evidence for your idea incrementally through testing as you move from concept to real-world action. For example, look at this workbook from IDEO's human-centered design experts.

Structured experiments help build evidence for translating an idea into wide applications. The pocket-card principles still apply: plan a change, predict the impact, try the change, contrast your prediction with actual results, and decide what to do next based on your study.

However, two additional experimental design principles will help you demonstrate the impact of a new idea across multiple settings and teams:

Make comparisons local in time, place, and equipment.

Randomize the assignment of treatments to experimental units.

A simple experimental design to compare two levels of an intervention—for example, a “treatment” based on the new design and a “control” based on current practice—integrates these principles.

Identify pairs of experimental units that you believe are similar on relevant attributes—staff members, care teams, hospital units, clinics.

Randomly assign one unit in each pair to the treatment and the other to the control. While there may be large differences between pairs, by construction, there will be relatively low differences within each pair.

Estimate the treatment effect: calculate the difference between the treatment and control within each pair and take the average over all the pairs.

If you have only one pair of units, random assignment still provides a stronger basis for assessing the treatment’s impact than simply comparing a single unit's performance before and after the treatment intervention.

Example

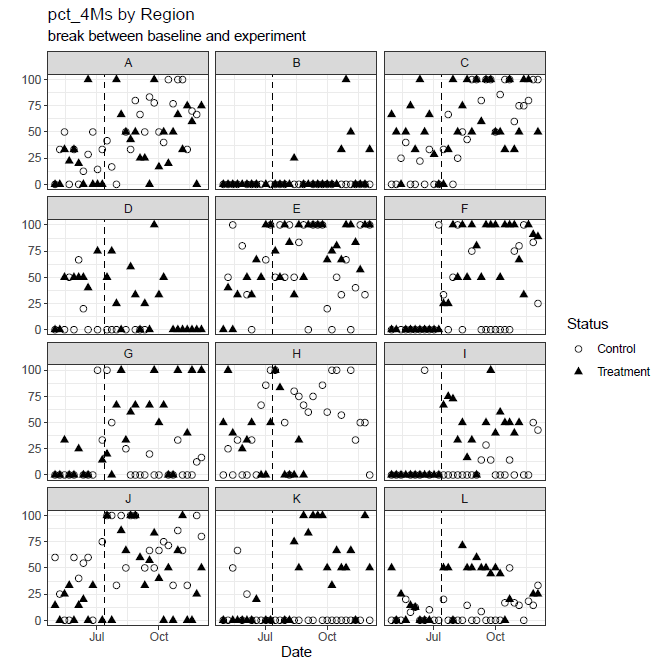

We used a randomized pair design two years ago to demonstrate the effectiveness of a training intervention in aligning primary care visits with a standard 4Ms-based protocol. We studied a 12-region subset of a multi-state health system. In each region, we identified a pair of clinicians with similar performance, as measured by visit volume and baseline protocol use. We asked a manager in each region to assess whether the two clinicians were comparable in experience and availability for an eight-week program. If the manager did not consider the clinicians to be roughly equivalent, we sought replacement candidate(s) who would meet the equivalence requirements.

Once we had a pair of roughly equivalent clinicians, we randomly assigned one clinician to the “treatment,” coaching by the local manager that applied a set of process tips and materials developed over three test cycles by training leaders.

The “control” clinician would continue to experience “usual” management support and performance feedback.

The effect of the intervention is the difference between the percentage of treatment clinician visits aligned with the standard protocol and the percentage of control clinician visits aligned with the standard protocol.

While we knew that regions varied on multiple characteristics, within each region’s pair of clinicians, conditions were relatively more homogeneous. A within-region comparison of treatment and control results increases the experiment's sensitivity to detecting the treatment effect.

Randomization averages out unmeasured factors that might affect visits, reducing the likelihood that factors other than the treatment caused changes in performance.

Randomization also enables a technical assessment of whether the observed differences could have arisen by chance, assuming no treatment effect.

To ensure that averaging did not obscure important patterns in performance, we began our analysis with time-ordered plots. Within each region, we have two series, treatment and control. The plot patterns raised additional questions that required more digging to understand.

With additional summaries and detective work, we demonstrated that across the 12 regions, the intervention led to an average 20% increase in compliance. The experiment gave a realistic assessment of the proposed coaching intervention, sufficient to guide management decisions.

Anniversary Note: 90 years of experimental design theory and practice

In 1935, R.A. Fisher published Design of Experiments, in which he presented the fundamentals of modern experimental design, rooted in his experience with agricultural trials.

Fisher was both an influential scientist and a pioneer in 20th-century statistics. He combined mathematical insights and years of work at the Rothamsted Experimental Station in Great Britain to shape his experimental theory.

A century ago, agricultural experimenters struggled to efficiently select varieties of plants or types of cultivation (treatments) that would yield higher quality grains, vegetables, fruits, and fiber. Local variation in fertility across field sections makes it difficult to detect small but commercially meaningful differences between treatments. Yearly differences in weather conditions compounded the challenges.

Fisher’s methods eased the struggles. He outlined practical ways to reduce the impact of large sources of variation in field plots and planting by effective grouping (“blocking”) and adjustment using baseline measurements. The simplest example of blocking is the pairing we described earlier. He advised experimenters to randomize treatment assignments across field locations. Randomization averages out the unknown or uncontrolled effects of soil fertility variation. It provides a rational basis for assessing whether observed treatment effects could have arisen by chance if, in fact, the treatments do not affect system performance.

While later chapters of Design of Experiments include more mathematics than most general readers may enjoy, Chapters II, III, and IV outline Fisher’s arguments for randomization and grouping with hardly any equations. He uses his invention of analysis of variance in straightforward terms, so you can follow along even if you never learned (or have forgotten) the details.

Notes

1. Summarizing Toyota's approach to scientific thinking, Mike Rother created a pocket card for daily experimentation; get it here. The Helena managers used a version of Rother’s pocket card to guide their thinking.

2. Healthcare operations experiments present more inferential challenges than experiments with molecules, machines, or plants. Often, studies are not blinded to participants; social-psychological factors may contribute to observed treatment effects. Also, structured experiments that extend beyond a local quality-improvement focus may constitute human-subjects research and require compliance with host-country regulations.