A Culture of Learning

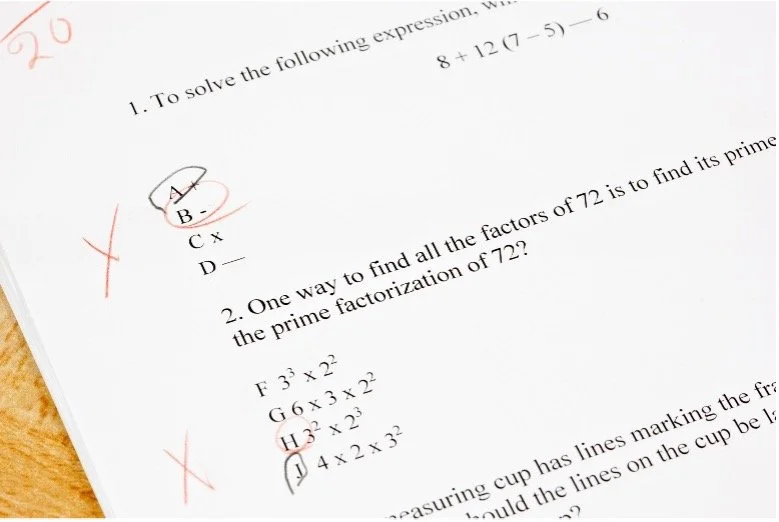

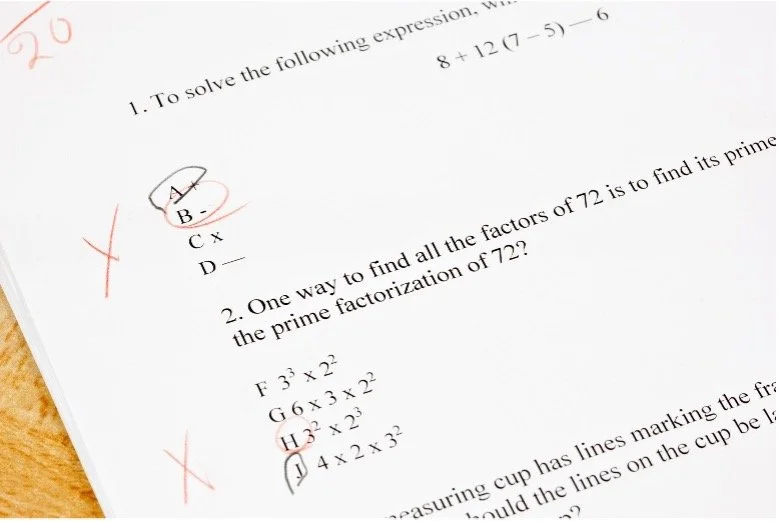

Does the picture of a marked-up math test paper make you anxious? I taught high school math at a suburban Connecticut public school as my first full-time job. I used a red pencil to circle errors on test papers.

A recent preprint by a team of researchers led by David Yeager, a psychologist at the University of Texas at Austin, summarizes an experiment that teaches math teachers to embed their testing and feedback in a “culture of learning.”

While the research would have helped my students and me 50 years ago, the report has lessons now for my work coaching people to improve healthcare. In a range of workplaces, the research team notes: “…a culture of learning could promote innovation and increase employee satisfaction and well-being.” [p. 2]

Also, aligned with my interest in designing effective tests, the report presents a worthy model for conducting and analyzing a social psychological experiment.

The FUSE Research

Yeager’s team worked with 6th-9th-grade math teachers in Texas.

“[The intervention] motivated and coached teachers to cultivate a ‘culture of learning.’ This was intended to contradict the typical, disengaging ‘culture of judgment and evaluation’ in secondary schools. The program, called the Fellowship Using the Science of Engagement (FUSE), influenced teachers’ light-touch practices and involved changes to classroom language and communication around student mistakes, confusion, and grades.” [p. 1].

The school-year-long experiment involved 152 teachers who taught 12,000 students. The team randomized teachers to either a treatment group guided to build a culture of learning or a control group that received education on cognitive strategies and classroom application, with no effort to address classroom culture.

The top-line results:

“[The intervention] led to an estimated effect on student math performance equivalent to an additional 4 months of student learning, and reduced the proportion of teachers who reported feeling ‘burnt out’ by half, while improving teacher well-being… Given the relatively low cost of the program (~$25 per student per year) this study highlights the ability of behaviorally-informed interventions to influence teachers’ subtle, culture-building practices and points to their role as an important route to educational improvement.” [p. 1]

While social psychology has suffered from a replication crisis, in which headline results disappear when follow-ups fail to replicate the claimed effect, this study is well-designed, with its impact estimates supported by a conservative analysis.

Importantly, this experiment was not a “one-off” trial that might have shown an impact just by chance. Rather, the team’s experiment is the latest iteration between theory and experimental data:

“… the present study represents a success story for cumulative, reproducible, and transparent research. The FUSE program had its origins in pre-registered RCTs showing that student growth mindset interventions were more effective among teachers with more of a growth mindset, and less effective among teachers with more of a fixed mindset. Next, pre-registered studies manipulated teachers’ fixed vs. growth mindset messages to students, using randomized experiments, confirming the causal results of the measured moderator in previous studies. That program of research yielded a new theoretical model, the Mindset x Context framework, which in turn informed a long process of qualitative and observational research to identify the FUSE teacher practices that would best support students’ mindsets. Ultimately, this line of work yielded the present culture of learning principles and practices at the heart of the FUSE program. Finally, here we showed that motivating a new group of teachers to use those culture-of-learning practices and supporting them in that implementation with a virtual network and fellowship could improve student engagement and performance, most strikingly among the fixed mindset teachers who were the targets of the initial research.” [p. 17]

Connection to Improvement Coaching

Build a Culture of Learning

Teachers in the culture-of-learning treatment group learned five practices. The first practice is at the heart of effective improvement, “mining mistakes as learning opportunities.”

Solving problems in a clinic, hospital, or home care starts with recognizing a gap between current and desired performance. Failures, errors, mistakes, waste, and stress are typically deviations from effective, safe, and efficient care. These deviations are the raw ingredients for improvement.

My experience and current advice to healthcare teams embody the guidance I received from my improvement teachers 40 years ago: view failures as “mountains of treasure.”

Isao Kato, a major contributor to the development of the Toyota Production System, challenged managers to design the work environment so mistakes and mismatches between the current and desired states were easy to see—pile up the mountain of treasure, no extra digging required.

A culture of learning in the math classroom encourages teachers to surface students' thinking, validate what students did right, and then build on that understanding. [Supplementary Materials, p. 22]. A culture of learning in any workplace will identify what is correct about the current situation, seek to build on what’s working well, and modify conditions and actions to improve performance.

Integrate Changes with People’s Values

Yeager’s team asked teachers to change behavior: what they said, how they reacted to student mistakes, and how they analyzed errors with students to get closer to desired outcomes.

“… the problem of professional behavior change, in general, is a large one, with many touted and popular programs failing to influence workplace behavior in rigorous experiments. We suspect that the FUSE approach was effective where other programs were not in part because it used the values-alignment method of persuasion. Values-alignment holds that it is generally more effective to reframe a behavior as being consistent with a group’s core values, rather than trying to change what they value. Here we used this approach to address something teachers already cared about deeply: obtaining the willing engagement and learning of students in their classrooms, without coercion. By framing FUSE as a means to attain what, to teachers, was a core criterion for professional status and respect, then the program was able to instill greater and more lasting changes in teachers’ beliefs and attitudes and behaviors.” [p 16.]

A specific pause to consider what clinicians, healthcare administrators, and support staff value and to reframe proposed changes to align with those values seems like a worthy addition to the standard work of healthcare improvement. A value-alignment reflection is certainly worth testing.

Study heterogeneity intentionally

Attention to heterogeneity is a fancy way to advise improvers to understand the limits of a current intervention: where, when, and with whom it works or fails. That’s sound advice to developers of interventions, which will help us give honest and reliable advice to people considering adopting and adapting proposed changes.

The researchers paid careful attention to variation in outcomes across teacher, student, and school subsets in both the design and analysis of their experiment. Understanding this variation is essential to the effective spread of a promising intervention.

The intervention's strongest effects were observed among teachers with a prior “fixed” mindset in high-performing schools. (“Fixed mindset” is the belief that a student's math ability is fixed and cannot change.) Furthermore, although teachers, not students, were the experimental unit, supplementary analysis of student performance by race showed larger performance gains for Black students than for white students, while prior disparities between white and Black students in perceived teacher respect essentially disappeared. (p. 15-16)

Yeager’s team recognized that a simple model focused on an average effect comparing treatment and control groups does not adequately reflect the heterogeneity of teachers, students, and schools in a school district or state. To skirt the implications of Rossi’s Iron Law, the wider application of the FUSE intervention needs to accommodate this heterogeneity.

“The present research therefore serves as an empirical example of the value of systematically studying heterogeneity in field experimental research—first correlationally, later using laboratory methods, and finally using a scaled-up field experiment that manipulates a previous moderator. Heterogeneity is not, as some have claimed, solely a secondary analysis that researchers conduct to salvage an otherwise-ineffective study. Instead, we argue that the analysis of heterogeneity should be at the core of how behavioral scientists routinely conduct their programs of research, so that more reliable and impactful solutions can be discovered. The fact that in the present research this process yielded an intervention that addressed problems that so far have eluded behavioral scientists—while also suggesting novel methods for changing workplace culture—supports our claim that a rigorous approach to studying heterogeneous effects of behavioral-science-based interventions, aided by modern statistical methods that reduce the chance of false-positive results, can play a useful role in the field’s search for large and lasting impacts on policy-relevant outcomes.” [p. 17]

References in the Preprint

The preprint cites 80 references that deserve study. The excerpts from the preprint included in this post each footnoted multiple references, which, for clarity of presentation, I excluded. Get the preprint and track down the references.

Technical Note

The report uses Bayesian Causal Forests (BCF) as the primary method for analysis and impact estimation. I’m eager to learn more about BCF and how it can support causal inference.